Excerpt from the foreword to the catalogue Dimensions of the Surface:

Dimensions: Associations with the Work of Nita Tandon

[…] As I was sitting in Nita Tandon’s studio asking her about her work, I found myself sitting opposite one of her works: a door built into a wall. Just as this book documenting Nita Tandon’s work is called Dimensions of the Surface, the door in the wall corresponds to that title. The door consists solely of its own surface; it cannot be opened and, therefore, it cannot be closed. As an artwork it is ostentatiously factored out of the usual exploitations, and unfortunately that is true also with regard to any hermeneutic exploit-ations: the door in the wall neither invites you to express an opinion about it, nor does it prevent any measure of interpretation.

Ever since I began studying philosophy I have had something of a hermeneutic tick, a slight compulsion (whenever an opportunity arises) to interpret what is already visible. Take doors or bridges, for example. These are metaphors – and no minor ones at that; indeed, in dimensional terms they could not be greater: being able to step inside, being shut out … As the idiom goes, every door is an opening. And yet, occasionally, a door does stay closed.

Franz Kafka was a lawyer, and as a writer he is probably the most famous opponent of any form of wishful thinking about the law, which would have us believe that the law is open to everyone. As Kafka writes in one of his parables, ‘Before the law stands a door-keeper. A man from the country comes to this door-keeper and asks for entry into the law. But the door-keeper says he cannot grant him entry now. The man considers and then asks if that means he will be allowed to enter later. “It is possible,” says the door-keeper, “but not now.”’

This indication of time holds out the prospect of the man gaining admission at some point; it is a postponement to the future. It also means that the enquirer is referred to an activity which, by its very nature, is most strange in that it is based on passivity – that is, on waiting. I have in my possession a postcard featuring the likeness of [Bavarian comedian and cabaret performer] Karl Valentin and a quote by the comedian, a kindred spirit of Kafka’s. It reads, ‘At first I waited slowly, but then ever more quickly.’ Indeed, as time runs out, it becomes crucial to wait faster and faster. And the man in Kafka’s parable waited and waited, but there’s a limit to how much a man can wait – after all, his death comes ever closer. As a dying man, the character in Kafka’s tale Before the Law finally gets an inkling of the sort of question he might have to ask in order to find out what was happening to him: ‘“But everybody strives for the law,” says the man. “How is it that in all these years nobody except myself has asked for admittance?” The door-keeper realises the man has reached the end of his life and, to penetrate his imperfect hearing, he roars at him: “Nobody else could gain admittance here, this entrance was meant only for you. I shall now go and close it.”’ […]

Regal lautet der Titel dieser Arbeit, die Nita Tandons Beitrag zu einer von ihr kuratierten Gruppenausstellung war, die im Untergeschoß ihres Ateliers stattfand. Die Unzugänglichkeit von Raum und

zur Arbeit benötigtem Material während der Vorbereitungsphase und der gesamten Dauer der Ausstellung wurde zum Gegenstand dieser Arbeit. Tandon verstaute die Materialien, mit denen sie gearbeitet hatte, zusammen mit den unfertigen Werken in einem großen Regal, das im Ausstellungsraum eingebaut war, sodass das Kunstwerk und die Voraussetzungen für seine Produktion, Aufbewahrung und Archivierung in einem Objekt vereint waren.

Digging out a historic lawn creates a bed for an air-filled, velvety, undulating body. Removing a section in a sprawling park draws the sculptural image out of its intimate environment and exposes it to public view. Depending on the distance from which it is viewed, this inviting ‘bed’ is reduced to a sheer line or becomes an exposed body deprived of its protective indoor space. However, on stepping onto Air Craft the viewer crosses a thin line between stability provided by the firm ground of the lawn and the instability of the body filled with air.

Excerpt from “As idle as a painted ship” by Edith Futscher from the catalogue Dimensions of the surface:

Made of white Formica and open at the top, Within and Without […] conjures up the impression of a locked space or movement that has been rendered impossible, as if aiming to conceal the existence of a room within. Yet in each case we have already entered this inner space that sparked our curiosity, for it has been turned inside out to form the exterior space where we just happen to find ourselves.

Excerpt from:

As Idle as a Painted Ship …

Movement and its Negation

in the Work of Nita Tandon

by Edith Futscher in the catalogue Dimensions of the Surface, p. 42 – 51

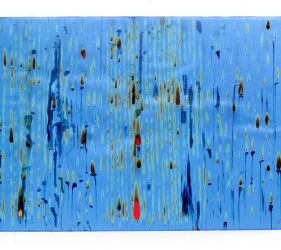

[…] movement comes into its own in Departure of the Fleet (2006, pp. 140/141). And it is no surprise that with reference to William Turner’s late painting of the same name (1850), this movement has a sense of ominous foreboding. For the departure of Aeneas from Carthage – like Coleridge’s mariner, a type of Odysseus – also spells doom for Dido. Whereas Turner places the focus on Dido’s farewell, the port’s exit, and the sky golden above the sea, Nita Tandon shows us ships. She placed blue-coated glasses containing tea lights in a small Plexiglas box. Within the blue there are blank areas in the shape of sailing ships. When viewed in a darkened room, the candlelight suggests movement – a moving image beyond the movie – a flickering and bobbing with ‘clouds’ weighing down from the top. The fleet gathers momentum and we see the small ships lurching in succession – some in clear focus, others merging in blurred shapes. Intriguing is the suggestion of a staged scene, atmosphere, the distribution of light and colour, and the transformative powers of fire. And Nita Tandon is also interested in the way Michel Serres understands Turner, as a materialist and as someone who introduced the matter of his time to his imagery, an era when steamers were leaving the sailing ship behind: ‘Turner or the introduction of fiery matter into culture. The first true genius in thermodynamics.’ 12 This fire engulfs the elements, especially its opponent water; it engulfs the picture, drawing, form, depiction. In Turner’s work the picture itself becomes a ‘furnace’.13 In Nita Tandon’s Departure of the Fleet the history of Dido and

Aeneas has vanished and probably the sailing ship as the sign of a bygone epoch along with it. Her tribute is not so much to this particular painting but to Turner’s consistency in drawing our gaze to regattas sweeping past like weather fronts. On the one hand, these cannot and could not hold their own against fire; on the other, they pose a challenge to eyes that seek to capture and contain.

In Departure of the Fleet Nita Tandon also explores a picture as well as the picture per se. Although in experimenting with various materials, such as concrete, Plasticine, text, and fire, she is dealing with a class of objects, when taken as a whole her works present plenty of scope for that ever-topical question about what constitutes a picture, a term in the singular, a question that can be posed time and again, is repeated, and gives rise to a multitude of answers.

12 Michel Serres, Hermes: Literature, Science, Philosophy, ed. Josué V. Harari and David F. Bell (Baltimore and London: John Hopkins University Press, 1982), 57. Serres’s principal witness is Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire, Tugged to her Last Berth to be Broken Up, 1838, London, National Gallery.

13 Ibid., 61.

Human Resource or Zoran and Goran is a performative human sculpture specifically conceived for Northwest by Southeast. Two men selected randomly from workers walking the streets of Skopje in search of work. They were solely employed for the purpose of pumping air simultaneously into and out of an inflatable mattress. This highly strenuous act accompanied by wheezing and squealing sounds produced by air pumped through a valve and sucked out again underpinned the futility of effort. Paid the same wages as they would have probably received for illegal labour in Vienna, their work however achieved no results as the mattress never became entirely inflated nor entirely deflated despite their untiring efforts.