Excerpt from the foreword to the catalogue Dimensions of the Surface:

Dimensions: Associations with the Work of Nita Tandon

[…] As I was sitting in Nita Tandon’s studio asking her about her work, I found myself sitting opposite one of her works: a door built into a wall. Just as this book documenting Nita Tandon’s work is called Dimensions of the Surface, the door in the wall corresponds to that title. The door consists solely of its own surface; it cannot be opened and, therefore, it cannot be closed. As an artwork it is ostentatiously factored out of the usual exploitations, and unfortunately that is true also with regard to any hermeneutic exploit-ations: the door in the wall neither invites you to express an opinion about it, nor does it prevent any measure of interpretation.

Ever since I began studying philosophy I have had something of a hermeneutic tick, a slight compulsion (whenever an opportunity arises) to interpret what is already visible. Take doors or bridges, for example. These are metaphors – and no minor ones at that; indeed, in dimensional terms they could not be greater: being able to step inside, being shut out … As the idiom goes, every door is an opening. And yet, occasionally, a door does stay closed.

Franz Kafka was a lawyer, and as a writer he is probably the most famous opponent of any form of wishful thinking about the law, which would have us believe that the law is open to everyone. As Kafka writes in one of his parables, ‘Before the law stands a door-keeper. A man from the country comes to this door-keeper and asks for entry into the law. But the door-keeper says he cannot grant him entry now. The man considers and then asks if that means he will be allowed to enter later. “It is possible,” says the door-keeper, “but not now.”’

This indication of time holds out the prospect of the man gaining admission at some point; it is a postponement to the future. It also means that the enquirer is referred to an activity which, by its very nature, is most strange in that it is based on passivity – that is, on waiting. I have in my possession a postcard featuring the likeness of [Bavarian comedian and cabaret performer] Karl Valentin and a quote by the comedian, a kindred spirit of Kafka’s. It reads, ‘At first I waited slowly, but then ever more quickly.’ Indeed, as time runs out, it becomes crucial to wait faster and faster. And the man in Kafka’s parable waited and waited, but there’s a limit to how much a man can wait – after all, his death comes ever closer. As a dying man, the character in Kafka’s tale Before the Law finally gets an inkling of the sort of question he might have to ask in order to find out what was happening to him: ‘“But everybody strives for the law,” says the man. “How is it that in all these years nobody except myself has asked for admittance?” The door-keeper realises the man has reached the end of his life and, to penetrate his imperfect hearing, he roars at him: “Nobody else could gain admittance here, this entrance was meant only for you. I shall now go and close it.”’ […]

A Trace Dismantled

A video showing scenes of a deinstallation, two small boxes with thousands of squares of Plasticine, each the same size, is all that remains of Nita Tandon’s Fingerprint – Die Rückseite der Vorderseite [The Back of the Front]. Is Fingerprint a performance, an installation? Is it an object, a picture, or a sculpture? This defiance of classification is in no way a disruptive factor; to the contrary, it is the very subject of this work: a game of identity for which the oversized fingerprint serves the artist as a motif.

The fingerprint, a pixelated scan in four shades of grey, is made by pressing eight-by-eight-centimetre squares of Plasticine with the finger onto the large glass facade of Schauraum, the exhibition space of the University of Applied Arts, in a passage of Vienna’s Museum Quarter. The space itself remained unused during the entire course of the exhibition. However, visitors were allowed to enter the space at the opening and had the opportunity to see the back of an oversized fingerprint, which in contrast to its two-dimensional front was three-dimensional. Once again Fingerprint defied classification. It was exhibited for several weeks on the glass pane, where passers-by could only view its two-dimensional

front. It was not always apparent even from close quarters that the material used was Plasticine. Finally, the Plasticine was removed and the glass pane thoroughly cleaned. That precisely the process of deinstallation – usually not deemed worthy of documentation – was recorded on film by Nita Tandon is yet another reversal that further underscores Fingerprint’s temporary character.

Fingerprint robs us of all terms of description, or Fingerprint forces us to choose a definition. Nita Tandon thus succeeds in creating a definition of the term ‘identity’ for which she uses methods that are not analytical but purely synthetic, playing a game with identity of which nothing remains but memories of

a documentation of the deinstallation of a fingerprint.

Daniel Wisser, 2011

Regal lautet der Titel dieser Arbeit, die Nita Tandons Beitrag zu einer von ihr kuratierten Gruppenausstellung war, die im Untergeschoß ihres Ateliers stattfand. Die Unzugänglichkeit von Raum und

zur Arbeit benötigtem Material während der Vorbereitungsphase und der gesamten Dauer der Ausstellung wurde zum Gegenstand dieser Arbeit. Tandon verstaute die Materialien, mit denen sie gearbeitet hatte, zusammen mit den unfertigen Werken in einem großen Regal, das im Ausstellungsraum eingebaut war, sodass das Kunstwerk und die Voraussetzungen für seine Produktion, Aufbewahrung und Archivierung in einem Objekt vereint waren.

Digging out a historic lawn creates a bed for an air-filled, velvety, undulating body. Removing a section in a sprawling park draws the sculptural image out of its intimate environment and exposes it to public view. Depending on the distance from which it is viewed, this inviting ‘bed’ is reduced to a sheer line or becomes an exposed body deprived of its protective indoor space. However, on stepping onto Air Craft the viewer crosses a thin line between stability provided by the firm ground of the lawn and the instability of the body filled with air.

Excerpt from “As idle as a painted ship” by Edith Futscher from the catalogue Dimensions of the surface:

Made of white Formica and open at the top, Within and Without […] conjures up the impression of a locked space or movement that has been rendered impossible, as if aiming to conceal the existence of a room within. Yet in each case we have already entered this inner space that sparked our curiosity, for it has been turned inside out to form the exterior space where we just happen to find ourselves.

Reversing planes, aspect perception, making things that permit two ways of seeing are among the areas that Nita Tandon addresses in her work, regardless of the medium or material she uses. She is consistently not analytical in her approach, for she does not guide the viewer’s eye towards specific themes or contents but towards the gaze itself, towards our perception.

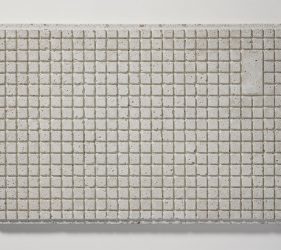

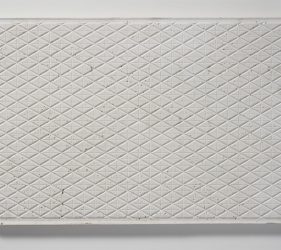

Also the objects from the Automats are series based in this concept – the title’s semantic ambiguity being part of their very appearance. What we have before us are concrete casts of car mats, rubber mats that we barely get to see while seated in the car. Negatives of these mats cast in concrete hang before us on

the wall, imprints of a surface that we do not ordinarily touch now mirrored in concrete. The original object’s tactility must now be replaced by the visual. The three-dimensionality of the object that had at first glance presented itself as a false picture can only convey an idea of the object’s haptic qualities.

Some of Tandon’s earlier works include ‘pictures’ (I have intentionally put this term in quotation marks) that combine painting and concrete elements, show trompe l’oeil perspective, making sensually experienceable the aporias in the question of whether a thing is two- or three-dimensional. This paradox is implicit in these works, which Tandon consistently expands by including the space in which they hang. The series titled Disclosure comprises objects that look like doors, or perhaps they are doors – false doors at any rate, for they are robbed of their function; they are integrated into the space rather than asserting themselves as foreign objects like art exhibits tend to do.

The Automats are yet another step in this direction as the objects are serial in character: Tandon uses the same mould for numerous casts with different combinations of sand and cement, lending each a different quality. In this way the imprint of the objects, which gives a poetic turn to the trivial, results in a series that reverses this principal by giving a trivial turn to the poetic.

Daniel Wisser 2014